My Grandad - A Civil Rights Activist During A Turning Point In Our United States History

After a long and fulfilled life, my grandfather passed away earlier this year. I have taken on a family photo archival project where I’m going through his old boxes of photos and scanning them to share with the extended family. I am reminded as I go through his important letters, newspaper articles and photo’s just how much he was dedicated to the civil rights movement. I thought I would take a moment to share with you a little about why I’m proud of my grandfather.

On February 24, 1964, my grandfather, William S. Jones was installed as the pastor of a 140-member Presbyterian church in Asheville, N.C. He was the second white minister to be called to a black congregation in the South during the early years of the Civil Rights Movement, according to my grandmother Jean Jones. The congregation and the community welcomed him and his family immediately. "It put us at the forefront of the Civil Rights movement in that area of the South. While there was certainly tension, thankfully, the only overtly unwelcome experience we had was a flyer produced by the Ku Klux Klan about Martin Luther King, Jr. which was left in our yard in the early days of our arrival.", my grandmother told me.

In order to push the Asheville school system to actually integrate schools, my grandparents sued the Asheville board of education stating that their daughter’s education was being impacted negatively. I could not be more proud to have grandparents on the right side of this important issue during such a critical time in our nation’s history. There is clearly still room for improvement, but I am very proud of the work my grandparents did in the turbulent 50’s and 60’s.

The first white minister to be called to a black church was a friend of ours from seminary and he went to a Presbyterian Church in Raleigh, NC. Your granddad was the second, and the third was another friend of ours from seminary who went to a Presbyterian Church in Richmond, VA. We were all passionate about making the world better, about getting rid of racial bigotry, and about a cause to which we could devote our lives. We were young, idealistic, and committed.Over the next few years, Bill worked on a number of Civil Rights issues. He sought equal rights opportunities for all people in jobs and housing, and was instrumental in welcoming the independent federal government program called The Equal Opportunity Corporation to Asheville. Among other things, the EOC established Headstart as a federally-sponsored program for preschoolers from the age of one to five who lived in low-income areas of the city.

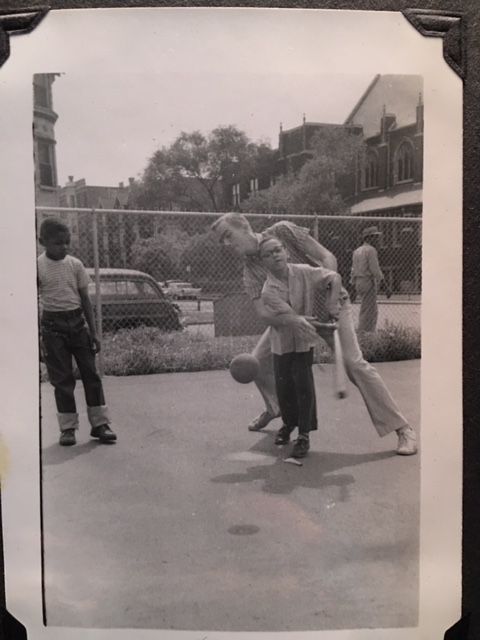

He worked to organize summer activities for the neighborhood children. Groups of college students from around the country would come and work with the children for a two-week period, and he led discussions with those college students about why he was doing the work he had chosen.

In 1967, Bill and his friend, Professor Merrill Proudfoot, who wrote the book Diary of a Sit-in which was published in 1962 drove to Hattiesburg, Mississippi to support the registration of black voters. Protesters and demonstrators had been arrested and jailed the week before their arrival and also the week after they left, but during the week that they were demonstrating, no one was arrested.

Bill and I joined a group of black parents in Asheville in a class action suit against the local school board which furthered the integration of all the local schools. The suit stated that our daughter, Cheryl, who was in elementary school was not getting a full educational experience because she went to an all-white school. The Asheville schools became integrated in a few years, both among students and among teachers. In another year, our second child, Tim, was the first white student to be enrolled in the class of a wonderful black teacher whose career took her to the central office of the school system in subsequent years. Tim loved her so much that he named his own daughter after her.

The Ku Klux Klan was active in the county outside of the city. After Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated, someone called our home and told me, “your husband will be next.” The threat, thankfully, was not carried out. Those were the years when a white woman named Viola Liuzzo was murdered for her efforts in voter registration in Selma, Alabama, when four little black girls were killed when their church in Birmingham, Alabama was bombed, when three college students were abducted and murdered in Mississippi simply because two were white and one was black, when James Reeb, a Unitarian Universalist minister was murdered for participating in the Selma March, and when many, many other such atrocities took place.

In 1968, the Asheville community honored Bill and two other people for their contributions and significant service to peaceful social change in the community. There was a big dinner with a crowd of community leaders. His portrait, along with other former pastors’ portraits, still hangs in the church he served in Asheville.